[Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Jared Gordon Follow @VCJG. Jared is an Investment Manager at IAF and is a lawyer by training (though we don’t hold that against him). The post summarizes Jared’s experience in both finding a gig at a Canadian VC fund and his conversations with others about these elusive positions. ]

It is that time of year again, when my inbox fills with requests for coffee from graduating students asking for two things: “How do I get a job in venture capital?” and “How do I get a “biz dev” job at a startup?” I always appreciate the initiative of people reaching out to me, but I thought I would share some tips to maximize everyone’s time.

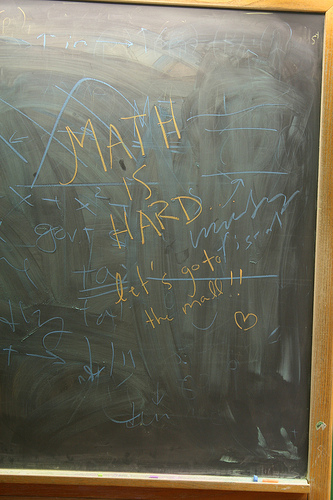

Getting a job in venture capital is hard.

It is not impossible. But it is very hard. If you are the kind of person who is interested in venture capital, you will probably ignore anyone who says the problem you are trying to solve is hard. If you are the kind who is committed you will also realize it is not about the money. We do it because we love working with startups.

There are not many funds out there, but at least that narrows the focus of your search. To give you a better idea, there are maybe 10 non partner venture capital roles in all of Canada. Everyone I know in venture capital has worked many years to get here. It requires drive, energy, time and a lot of networking. In truth, the only way to get a job in venture capital is networking.

The Difference between PE, IB and VC

The journey prepares you for the job once you get here. People I met with along the way are people I now do business with on a daily basis. Also, the job hunt is a chance to demonstrate to the community what kind of person you are and what kind of value you add.

Before we jump into the tips, there is a difference between PE (Private Equity) and VC (Venture Capital). Beyond the huge difference in compensation, VCs spend a lot more time understanding the dynamics of specific markets and verticals than they do on financial analysis. In PE you spend your time building and reviewing financial models. When working with startups, you spend some your time crafting financial models, however, the calculations and models are very different.

There is no template for working in VC

Some basic tips on how to network your way into venture capital are listed below. These tips are about how to get in front of the people you need to get in front of and how to make the most out of that meeting. There is no template for working in venture capital. Some of us have advanced degrees some don’t. Increasingly, having spent time at a startup is becoming more common. Having strong technical talent is a rare but desired commodity. If you can identify how technically hard a problem is, that will set you apart.

9 Tips to Getting a VC Job

- Don’t send a message over LinkedIn – This one is my primary pet peeve. A lot of the job of being a VC is being able to find information. Every investor’s email is available somewhere.

- Warm intros work best – Did I come to speak to your class? Did I come speak to your friend’s class? Do we know anyone in common? Anything you can do to create a connection between us will make me want to spend more time helping you.

- Don’t be scared to cold email – Cold emailing is a great skill to learn and have. You never know whose interest you might catch unless you try. Why not reach out to Fred Wilson? A partner at Kleiner who went to the same school/has the same interests as you? I find the cold emails that work best have great subject lines and can bring attention to something I, and the person I am emailing, have in common.

- NO FORM LETTERS – These are just insulting. You should be spending at least twenty minutes crafting each email. The person you are trying to get in front of has a linked-in profile/about.me page/bio somewhere. Use that information to show them that you value their time and advice enough to put some work into getting the meeting.

- Be persistent but not annoying – When I do not get a response from a warm intro, I follow up after a couple days. Some people have poor inbox management skills and stuff falls to the bottom. It is nothing personal. The person definitely saw your email and it shows persistence and that you value someone’s time when you follow up. With cold emails, if I do not hear back I will wait a couple days and send a quick second try. If I hear nothing, I leave it be.

- Be clear in your ask – The clearer and more direct you are about your ask, the easier it is for someone to know if they can help. Nothing is less appealing than a note asking to “learn more about venture capital.” The internet has cast the profession wide open, with more information available online now than was available to VC associates five years ago. You can learn about everything from VC funnel management, what the average day for a VC is like to the difference between European and American style waterfalls. Examples of good asks would be: “You are an early stage VC. While doing my MBA, I mentored startups and participated in Startup Weekend. Can I get half an hour of your time to talk about how I can transfer what I learned in school to a job or what else I can do to make myself a competitive candidate?” or “I want your job because I like working with early stage startups. Are you hiring? Can we make some time to chat so when you are, or when you know someone who is, you think of me?”

- Once you get the meeting, don’t blow it – You have only one chance to make a first impression.I spent the first months of my networking journey wasting a ton of important people’s time. I would sit across from them in boardrooms, coffee shops, and their offices and talk about myself for an hour.It took a meeting with Jeff Rosenthal of Imperial Capital to set me straight. He would not remember if you ask him, because the meeting was so bland. Jeff ended our meeting with some advice. He told me that everyone who got a second meeting walked into his office with a list of companies they would look to invest in. They proved they were capable of doing the job they were seeking. You can do that too.Look at the person you are meeting with and what spaces interest them. Use Crunchbase and Angelist to identify some promising startups and why you like them. Be prepared to defend your thoughts. This discussion is more interesting (and fun) then hearing about your involvement in the investment club or student government. One person I met with had a presentation he had put together on three trends in technology that he found interesting and why. They showed they were capable of hitting the ground running on day one.

- Follow up is key – Always make sure to send a thank you and take care of any action items you might have left the meeting with. If the person you are meeting with did not follow up on theirs, no harm in waiting a couple of days and sending a polite reminder.Following up does not end with the thank you note. It is always great to hear from people you have helped along the way about where they landed or how their search is going. This becomes especially important when it comes to the last tip…

- Coming close to something? BRING IN THE BIG GUNS!! – When you know there is a position and you have met with someone at the firm or submitted an application, now is when the networking pays off. You can make up for a lot of flaws in your resume by having someone you trust recommend you for a gig. If you treat your network right and maintain good relationships, they will have no problem making a call to get your application moved to the top of the pile.

This is where hard work pays off

Mark Suster summed it up in a comment on a blog post by Chris Dixon:

“The people who “sneaked into” the process were:

- great networkers

- great networkers and

- had other people contact me on their behalf (great networkers).

But if you don’t have GREAT street cred already don’t hassle the VCs. Just accept that it isn’t likely you’ll get in without doing great things at a start-up first.”

Chris Dixon agreed “Yeah, when I got my job in VC it was like a political campaign. I had one partner tell me ‘I’ve heard you[’re] a great guy from 6 people’ – which wasn’t an accident. I had done so many free projects, favors etc for VCs and startup and then I asked them to make calls on my behalf. It’s brutal.”

The venture capital community is a very small tight knit community. And the number of potential gigs is very small. It is a lot of effort to build the relationships and connections to get a job working at a venture fund. (Before you even consider this, you might want to brush up on Venture Math 101 and figure out why you really want to do this).

Additional Reading

Here are some great posts from people with more experience and authority on the same topic:

- Chris Dixon: Getting a Job in Venture Capital

- Seth Levine: How to get a job in Venture Capital – Revisited

- Alex Taussig: 3 Ways to Land a Job in VC

- Eze Vidra: So you want to be a venture capitalist?

- Guy Kawasaki: Venture Capital Aptitude Test (VCAT)

Still want some of my time? I am not going to tell you how to find me, but if you can figure it out, I look forward to chatting.

Photo Credit: Photo by Robert Couse-Baker – CC-BY-20 Some Rights Reserved